Of the abolitionists in early Oakland County, George Wisner was the most outspoken. As a journalist in New York, he had participated in riotous anti-slavery demonstrations. Inspired by a visit to his sister, he came to Pontiac in 1835 to study law. He became a prosecutor, Pontiac Courier editor, co-founded the Oakland County Anti-Slavery Society, and became a State legislator. Wisner used the Courier as an abolitionist force, making enemies of pro-slavery Samuel Gantt, resulting in a riot at a Pontiac anti-slavery lecture. Wisner died at age 37, shortly after moving to Detroit, and is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery.

George Wisner’s life was brief but bold. Since boyhood, he was headstrong and refused to back down from a position he believed in, which got him kicked out of his father’s house as a teenager, put him in the middle of a shootout at a New York newspaper as a young journalist, and made him enemies–as well as friends–in the early days of Pontiac anti-slavery politics. He took risks to fight (sometimes literally and physically) for the rights of enslaved people, and held others in public office to the highest standards of fairness and equity.

By 1837, Wisner had become an enemy of another newspaper editor and lawyer in Pontiac, Samuel Gantt. Gantt was a staunch Democrat, which in 1837 was a pro-south/pro-slavery political position. The two men used their newspapers to express their wrath and attack each other in print. As lawyers (Wisner had been elected prosecuting attorney) and residents of Pontiac, they also had public encounters in official and unofficial settings. Their feud continued unabated.

In February of 1837, Professor Cole (or Cowles) of Oberlin Institute in Ohio was invited to speak at a series of anti-slavery lectures for the Pontiac Baptist Church, which held its meetings at the county courthouse. Gantt (who some said was drunk) and a group of his backers attempted to disrupt the meeting by heckling the lecturer, arguing with him, and in general disturbing the presentation. He refused to leave when asked, and at one point pulled out a knife and waved it around. In the ruckus that developed between the two sides, one of Gantt’s backers hit George Wisner, who was prevented from retaliating by a friend. Professor Cole got the consensus of the audience to continue the lecture, and ultimately convinced many in attendance to support the anti-slavery cause. Within two days, Gantt’s paper, The Democratic Advertiser and Balance published an editorial accusing the abolitionists of starting the riot and denying any disruptive behavior on Gantt’s part. Wisner’s paper, The Pontiac Courier, responded with a detailed point by point description of the incident, clearly implicating Gantt as instigating the “riot.”4 A total of 33 men who witnessed the incident signed the statement as accurate. In the end, Gantt faded from the scene in Pontiac, while Wisner went on to become prominent with his legal colleagues, popular with voters, and a champion of Oakland County’s anti-slavery movement that established abolitionism as a foundation of public policy. 5

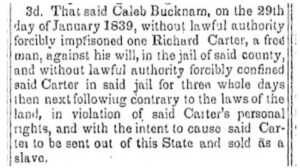

In an even more impressive case, in 1840, Wisner petitioned the Governor of Michigan to remove the elected Oakland County Sheriff (Caleb Bucknam) for what amounted to dereliction of duty on various charges, but more importantly, for unlawful arrest and detention of a free Black man, Richard Carter, who was visiting Pontiac, with the intention of having him sold into enslavement. Wisner’s case showed that Bucknam (who was a pro-slavery Democrat) detained Carter basically because of his race, without any evidence to substantiate that he was connected to a crime that had been committed in Detroit by a Black man. Furthemore, Bucknam had locked Carter in Pontiac’s jail and dragged out checking with Detroit authorities in a timely manner before learning he was not the right suspect and releasing him. Wisner claimed Bucknam’s objective was to transfer Carter out of state and into bondage.

Wisner was successful in the case, Bucknam was removed from office by Michigan’s anti-slavery governor, and Wisner publicly offered to represent Carter in a suit against Bucknam for damages. With modern eyes, the injustice in this almost 200-year old example of misuse of authority may be obvious, but this push by Wisner to seek justice for a Black man in these circumstances was unheard of at the time, even in the north. George Wisner was truly a man ahead of his time.

At his untimely death from what appears to have been consumption (tuberculosis), Wisner was mourned by fellow attorneys throughout Michigan for a full thirty days–also unheard of. A special proclamation was made before the State Bar of Michigan to acknowledge this unusual and brashly heroic man who believed in fundamental justice for every person.

For More Information

Article: George Washington Wisner and his Impact on Oakland County Abolitionism- by Donna Casaceli, Birmingham Museum

Acknowledgements

Primary research on George Washington Wisner by

Donna Casaceli, Birmingham Museum

Photo credit of George Wisner’s grave at Oak Hill Cemetery in Pontiac, Katie Neal

Narrative by Leslie Pielack

- Portrait of George Wisner in Sloan, William David. “George W. Wisner: Michigan Editor and Politician.” Journalism History, Vol. 6, No. 4, Dec. 1979, pp. 112–121, https://doi.org/10.1080/00947679.1979.12066929 ↩︎

- Sketch can be viewed on Wystan’s Flickr account, https://www.flickr.com/photos/70251312@N00/7517360202. Accessed 10/28/2024. ↩︎

- “Anti-Slavery Lecture,” The Pontiac Courier, 6 Feb 1837, p2. https://digmichnews.veridiansoftware.com/?a=d&d=OaklandPONTC18370206-01&e=——-en-10–1–txt-txIN———- ↩︎

- “The Riot,” The Pontiac Courier, 13 Feb 1837, p2. https://digmichnews.veridiansoftware.com/?a=d&d=OaklandPONTC18370213-01.1.2&e=——-en-10–1–txt-txIN———- ↩︎

- See Casaceli, Donna, “George Washington Wisner and his Impact on Oakland County Abolitionism” (Birmingham Museum, 2023). https://ugrr.mioaklandhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/George-Washington-Wisner-Impact-on-Oakland-County-Abolitionism-Casaceli.pdf. ↩︎

- “Impeachment of Sheriff Bucknam,” Pontiac Jeffersonian, 3 Mar 1840, p2. https://digmichnews.cmich.edu/?a=d&d=OaklandJFN18400303-01.1.2&e=——-en-10–1–txt-txIN———-. Accessed 10/13/2024. ↩︎